If you do sociology or, indeed, any social science whatsoever, you’ll come across the work of Erving Goffman. I have done too but never engaged with it as much as I should have done. This was brought back to me when I talked with somebody who once shared a taxi-ride with Goffman and chatted with him about his research. That somebody is my husband. He has never written down this story, so I offered him the opportunity to get some of it across in this blog.

I’ll first provide a quick overview of Goffman’s work and then hand over to my husband, David Clarke. After that, I say a bit more about Goffman and metaphors, as metaphors were, in a sense, his “tool of sociological analysis“.

A quick introduction to Goffman

“Erving Goffman (11 June 1922 – 19 November 1982) was a Canadian-born American sociologist, social psychologist, and writer, considered by some ‘the most influential American sociologist of the twentieth century’. In 2007, The Times Higher Education Guide listed him as the sixth most-cited author of books in the humanities and social sciences.” (Wikipedia)

Some of his most famous works are The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956); Asylums: Essays on the Condition of the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates (1961); Behavior in Public Places (1963); Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (1963); Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience (1974); and many more. Frame Analysis is perhaps the most important of his books for my own work on how metaphors, which are in a sense frames, emerge from overlapping conceptual frames of experience, organise how we think and act, and structure our perception of the world and each other.

How did Goffman achieve this fame? What new theory or method or even paradigm did he invent? Strangely, none of the above. He ‘just’ wrote very good essays on things he saw and thought about. Or, to put it in the words of one of his admirers and interpreters, Phil Strong (who never met him in person though): He refused “to link his work systematically to other academic traditions” or “to take part in the inter-galactic paradigm-mongering which conventionally passes for really serious sociology.” He loved observing and studying social interaction in all its messiness and to write about what he discovered.

It was at the height of Goffman’s fame that my husband met him by chance at a conference in Paris. He was a postdoc at the time and asked him some rather innocent questions about method, and Goffman asked him some innocent questions about money….

Remembering Goffman – by David Clarke

Once upon a time – the January of 1979, to be precise – a small meeting of social scientists was held at the European Laboratory of Social Psychology, in the Maison des Sciences de l’Homme in Paris, to discuss ‘The Organization of Human Action’. There were some very distinguished figures there, including Jerome Bruner, Rom Harré, and Erving Goffman. Michael Argyle, the famous Oxford social psychologist, was also due to be there, but he could not attend, and as a junior member of his research group I had the chance to take his place.

It was a ’round table’ meeting, and there was no audience except for the speakers, who presented papers to one another. At the end of the first day, we all set off into Paris to eat and relax, and by sheer chance, Goffman and I got separated from the group, and went off on our own. We shared a taxi through the streets of Paris – a city I did not know at the time – and ended up at a small café eating pizza and drinking wine for the rest of the evening. I will report the conversations that ensued, just as I recall them 46 years later, but with no further guarantee of the accuracy of the details.

I had read some of Goffman’s work and I knew he was a ‘big shot,’ but I had little idea of how important he was, or what a unique opportunity it was to talk to somebody who was – and is – relatively unknown outside his published work. So, I was able to bring a singular level of ignorance and naivety to the task as I chatted away to him.

As I was very early in my career and still looking for an approach that would suit me, I asked him what it would be to ‘do a Goffman.’ How would one set about it? By way of reply, he said that if you look at the history of the successful sciences, they start out with relatively informal methods. Biology didn’t begin with elaborate laboratories and instruments and measurements. It began with naturalists who wandered about in the wild, sketching plants and animals in a notebook, and maybe pressing the occasional flower between the pages. He saw his job as doing very much the same thing in the social world. He didn’t like experimental methods or quantification as applied to microsociology. He thought it was premature, if not irrelevant, and he was rather apt to poke fun at the foolishness of taking that approach at this stage.

Did he have armies of research students? No, he said he didn’t have much time for them, because they came in two varieties: the rather weak ones who needed a lot of attention and wasted your time; or the strong and capable ones, who could work on their own and not need the help of a supervisor.

It turns out he had been a research chemist before becoming a sociologist. (I am not totally sure if this is a recollection of our conversation, or something I found out from somewhere else.) One day, while working in his rather gloomy subterranean chemistry lab, and contemplating atoms and molecules, and the way they link, the way they form preferential bonds, and so forth, he emerged into the sunlight to take a brief lunch break. He was struck by the couples holding hands; the groups of friends chatting; and it occurred to him that this was the same phenomenon. The making and breaking of bonds; the forming of groups; and he realised that there was a whole new ‘chemistry’ to be done on the patterns of small-scale social interaction.

His books were hugely popular, and were read as serious academic works, and as enjoyable readable narratives by the person in the street. He was published in various countries, and in various languages, and had accumulated considerable royalties, often in the different countries involved. As he explained to me, he had accumulated a tidy sum in Britain, and then, riding along in the taxi, asked me, out of the blue, if I thought he should buy a block of flats in London. This took me by surprise, coming from a wealthy American whom I had never met before, and I cannot recall whether I offered anything very wise or well-informed in reply.

I later had occasion to consult the Social Science Citation Index for some unrelated reason. This was a multi-volume reference work in those days, which took up about three feet of library shelf with each year’s new volume, and it did the job that a Google search would do now. You could pick a known publication and look it up, and there would be a list of subsequent works in which it had been cited. I remember that well-known scholars would typically have entries that were two or three inches deep, in the fine print of those phonebook-like volumes. When I came to look for Goffman, his entries went on for page after page. I think it was something like six pages. This was a measure of the huge influence of the man, and the number of people who were reading and citing him.

In person he was nothing like I expected. I thought his detailed and incisive descriptions of the social world would be coming from someone who was obviously suave and sophisticated. Nothing could have been further from the truth. I have always described him to myself as a cross between Woody Allen and Columbo (the fictional TV detective). He was very funny. The formal conference was punctuated by witty asides and comments, often bringing us down to earth when academic self-importance was starting to take over. At one point, two of the delegates were engaged in earnest discussion, quietly to one side, and Goffman could be heard saying “Hey guys, do you two want to get a room together?”

I wish I could have met him again. I would appreciate it more, and would show more respect, but perhaps at the expense of the naivety which had stood me in such good stead on this occasion.

This is the end of David’s story….now back to metaphor…

Goffman, method and metaphor

Many books and articles have been written about Goffman and the way he wrote his books or rather essays about social interaction. It is well-known that he used a stage or theatre metaphor to explore how people interact with each other and construct their own identities, their selves, or hide them behind masks.

David and Goffman did not talk about that use of metaphor, but it’s clear that the movement of metaphor, that is, using one domain of knowledge or experience, say about natural history or chemistry or dramaturgy to do sociology and to write about what you find when doing it, was central to Goffman’s work (see Robin Williams “Sociological Tropes: A tribute to Erving Goffman“).

I’ll close with one personal communication about naturalism that Goffman conveyed in a letter to Phil Strong, which elaborates a bit more on what he told David during their taxi ride:

“[…] science, of the naturalistic kind, is exactly what I think I’m trying to do. My model for the device I use—the essay—comes in part from my regard for those of Radcliffe-Brown […] supported by an old aphorism of L. J. Henderson … that a single conceptual distinction could constitute a substantive scientific contribution. I am impatient for a few conceptual distinctions (nothing so ambitious as a theory) that show we are getting some place in uncovering elementary variables that simplify and order, delineating generic classes whose members share lots of properties, not merely a qualifying similarity. To do this I think one has to start with ethnological or scholarly experience in a particular area of behavior and then exercise the right to dip into any body of literature that helps, and move in any unanticipated but indicated direction. The aim is to follow where a concept (or a small set of them) seems to lead. That development, not narrative or drama, is what dictates. Of course nothing gets proven, only delineated, but I believe that in many areas of social conduct that’s just where we are right now. A simple classification pondered over, worked over to try to get it to fit well, may be all that we can do right now. Casting one’s endeavor in the more respectable forms of the mature sciences is often just a rhetoric. In the main I believe we’re just not there yet. And I like to think that accepting these limits and working like a one-armed botanist is what a social naturalist unashamedly has to do (E. Goffman, Personal communication).”

Strong went as far as to say, using, in a sense, a metaphor: “Goffman was the Linnaeus of interaction, the man who first began to bring serious conceptual order to the domain.” There is a lot more to say about Goffman and metaphor, but that’ll have to wait for another blog post.

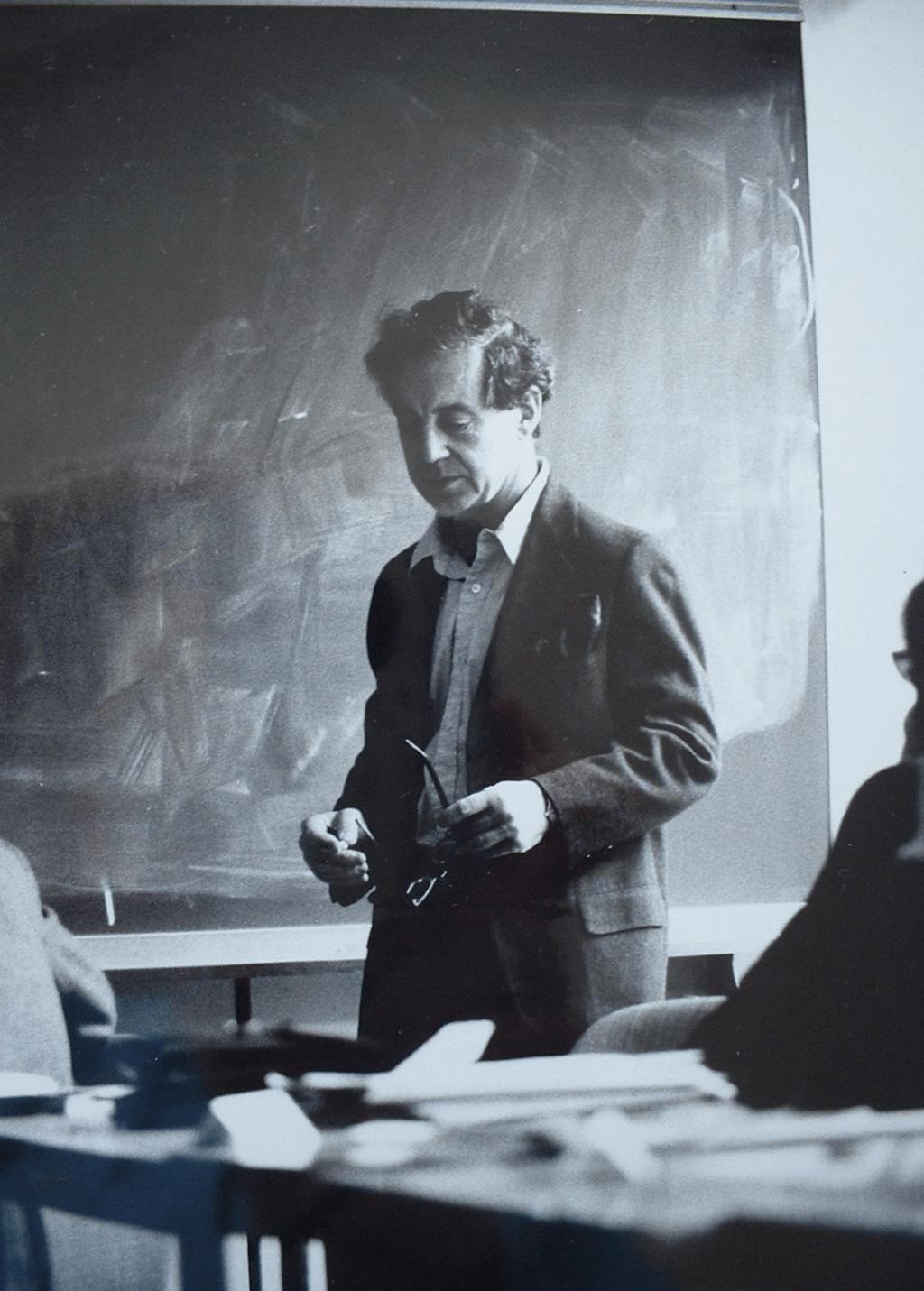

Image: Photo of Erving Goffman taken at the 1979 conference in Paris by Peter Collett. Reproduced here with permission

Further Reading

Robert Dingwall, former editor of the journal Symbolic Interaction, alerted me to a treasure trove of other anecdotes about Goffman, including one by himself which is well worth reading. These are collected in the interesting archive of Goffman’s life and work established by Dmitri Shalin at UNLV in the section entitled ‘biographical materials’.

Leave a reply to bnerlich Cancel reply