Years and years ago, I had an Academia profile in which I mentioned that when I began studying French literature in the mid-1970s I fell in love with Baudelaire and Rimbaud. I no longer have access to Academia, but somebody must have seen that sentence and recently sent me an email asking how I got from symbolism to metaphor analysis and science communication. That made me think: How did this happen? This post is an attempt to pull out this invisible thread running through my rather chaotic academic life.

This is a personal story, but it touches on more general topics, such as chance encounters, accidental discoveries and serendipity in academic careers; interdisciplinary working across the humanities, social sciences and natural science; and how knock-backs sometimes end up pushing you in unexpected but ultimately interesting directions.

From symbolist poetry to metaphor

I encountered the 19th-century symbolist poets Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud during my first semester of studying French literature at the University of Bonn in 1975. At that time, metaphor was still taught as a ‘figure of speech’ or a ‘trope’ and cognitive linguistics and conceptual metaphor analysis were not yet on the horizon. So, what’s the invisible thread leading from symbolist poets to the study of how language shapes thought, science and action through metaphors?

Rimbaud and Baudelaire were masters of using metaphors and symbols to create new meanings and experiences that cannot be captured by literal, straightforward language. Baudelaire’s concept of “correspondances” – the idea that different sensory experiences and realms of experience mysteriously echo and reflect each other – is fundamentally about how one thing can stand for or evoke another, which is the essence of metaphorical thinking.

Here is an evocative passage from Baudelaire’s famous 1857 Les Fleurs du Mal – ”Correspondances” (The Flowers of Evil/Correspondences):

La Nature est un temple où de vivants piliers

Laissent parfois sortir de confuses paroles;

L’homme y passe à travers des forêts de symboles

Qui l’observent avec des regards familiers.

Nature is a temple where living columns

Let slip from time to time uncertain words;

Man finds his way through forests of symbols

Which regard him with familiar gazes.

Rimbaud took this even further, famously writing about the systematic “derangement of all the senses” and using wildly inventive metaphors to try to access new forms of perception and truth. In 1871 he wrote a famous poem “Voyelles” – “Vowels”, later published by the poet Paul Verlaine in 1883, in which he explores synaesthetic imagery, like “A black, E white, I red, U green, O blue”, and treats language itself as having metaphorical, almost magical correspondences.

In 1985, ten years after my encounter with symbolism, I first encountered the work of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, the godfathers of modern metaphor theory. I was giving a tutorial on general linguistics at Wolfson College Oxford, when my tutee pulled a book out of his satchel and asked: “Have you read this?” The book was Lakoff and Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By, published in 1980. I read it immediately and never looked back, forgetting all about Rimbaud and Baudelaire.

I began to see that metaphors aren’t just decorative rhetorical devices that one has to memorise, like ‘litotes’ and ‘chiasmus’ etc., but that they shape how we think, understand abstract concepts, and communicate about complex topics like science. One can almost say that this new dawn in metaphor studies was like a more systematic, analytical extension of what those symbolist poets were doing intuitively. They understood that metaphor is fundamental to human cognition and meaning-making, not just a poetic ornament.

It seems that my move from loving Baudelaire and Rimbaud to studying metaphor in linguistics and later science communication (we come that), and from experiencing the power of metaphor as a reader to understanding how that power works as a scholar, was perhaps not as surprising as I always thought.

But what about science and science communication? How does that fit into the various threads of my academic life. That’s another story, to which we come via another part of the invisible thread.

From symbolist poets to contextualist linguistics

In the 1980s I had ended up in Oxford by accident. This is how that came about:

After studying French literature, I had moved into French linguistics, and I had also moved away from Rimbaud and Baudelaire to Ferdinand de Saussure and Ludwig Wittgenstein. As a sideline to my PhD on the history of pragmatics in France, I published one of my first academic articles in 1983 under the title: “Le même et l’autre: Le problème de l’identité en linguistique chez Saussure et Wittgenstein” which was, if I say so myself, quite profoundly philosophical – and getting me back to exploring ‘correspondences’.

I was just finishing the article when I stumbled upon a book by Roy Harris, then professor of general linguistics at the University of Oxford, entitled Language Myth (1981) which also dealt with the issue of linguistic identity. I quickly included a footnote to this book in my article just before publication.

At the same time, I was visiting my sister in Oxford where she was working as a language assistant and mentioned this to her. She took note and when I finished my PhD in the history of French linguistics in 1985, she sent me an advert for a Junior Research Fellowship at Wolfson College in general linguistics. I wrote my application, submitted my article as supplementary information, Roy Harris read it, invited me for interview and that’s how I ended up in Oxford.

But now back to symbolist poets. Thinking about the invisible thread in my academic life, it now occurs to me that both symbolists and contemporary metaphor theorists challenge the idea that language is just a transparent vehicle for pre-existing thought. Now, that was exactly what I discussed a lot with Roy Harris who had published another book in 1980 entitled Language Makers and was engaged in developing his critique of the ‘telementational’ model of communication (the idea that language is just a conduit for transmitting ready-made thoughts from one mind to another). This later became what he called ‘integrational linguistics’.

Integrational linguistics is an approach to language that views it as a process of social action rather than a static system of rules, emphasising the context of communication and the integration of verbal and non-verbal activities – a type of thinking I had tried to trace in my historical studies of semantics and pragmatics. We were both interested in studying linguistic acts within their communicational settings, him from a theoretical, me from a historical perspective.

We also discussed Saussure and Wittgenstein and taught seminars at Worcester College about the arbitrariness of the sign, the nature of linguistic value, and how language constitutes rather than merely represents reality.* All this challenged the idea that meaning is fixed and pre-exists communication. It all connects, if you think about it, quite beautifully to how metaphor creates understanding rather than just decorating pre-existing ideas.

This highlights a nice trajectory from the symbolist poets, Rimbaud and Baudelaire, who intuitively grasped the creative power of language, through Harris’s rigorous philosophical critique of transmission models of meaning and communication, to me studying the hidden histories of semantics and pragmatics and later on how metaphors shape scientific thought and public understanding. It’s all about language as constitutive and creative rather than merely representational.

From history of linguistics to science communication

While in Oxford, I continued my work on the history of linguistics, focusing on the history of semantics (the study of meaning) and pragmatics (the study of language as action) another part of the invisible threads running through my academic life. It was absolutely wonderful to dig deeper into the history of pragmatics, moving from French to English traditions, and rummaging around in J. L. Austins‘s, of How to do Things with Words fame, manuscripts and notes (Austin was the tutor of John Searle and Rom Harré who, in turn, collaborated with my future husband…). These rather esoteric undertakings had two, initially invisible, advantages.

Researching the origins of semantics gave me quite a deep insights into philosophical and linguistic thinking about metaphor and metonymy, not only as mechanisms underlying the historical evolution of meaning, but also as mechanisms of thought and language, from Aristotle to Giambattista Vico to Friedrich Nietzsche and more. I therefore had quite a good historical and theoretical grounding once I homed in on modern metaphor theory and cognitive linguistics.

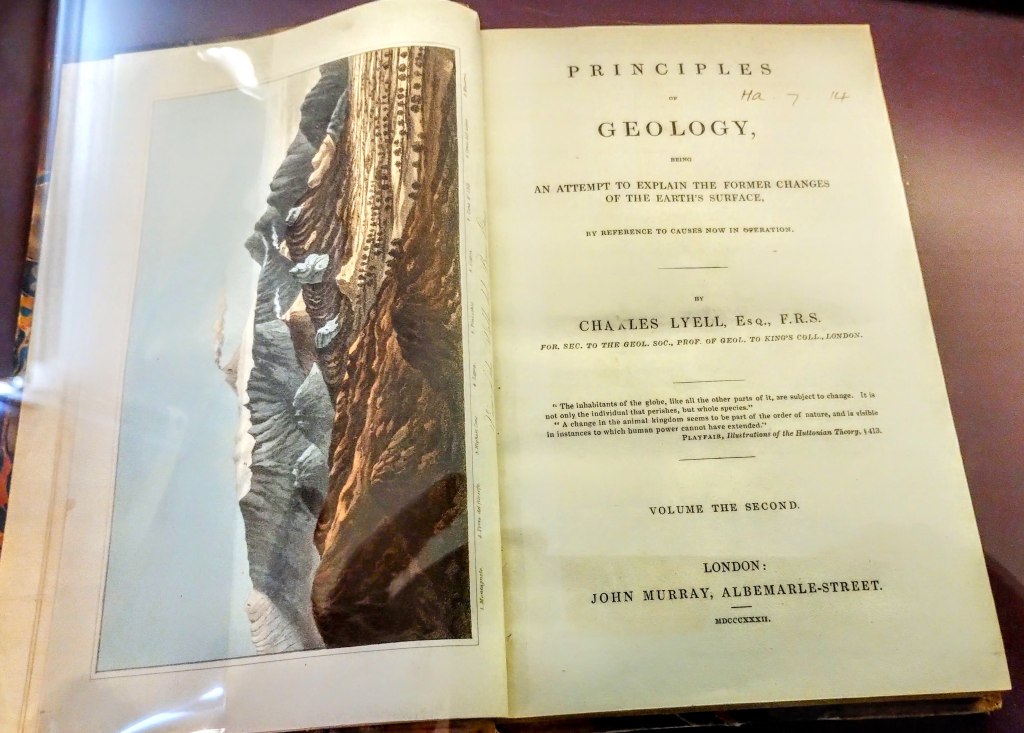

The second advantage was that trying to fathom the origins of linguistics more generally, from about 1780 to 1930, brought me into contact with lots of other sciences emerging at the same time, such as biology, geology, psychology and so on, from Darwin to Lyell to Wundt and so on, sciences that all influenced each other. Little did I know that I’d come back to science more broadly later in life. (I was finishing this blog post while visiting Cambridge and that included a trip to the Sedgwick Museum where I reminisced about ‘correspondences’ between geology, biology and linguistics….).

At the end of the 1980s I moved with my husband to Nottingham, got two generous grants from the Leverhulme Trust that allowed me two write two books on the history of semantics and pragmatics, but then professional oblivion threatened, as getting a job in the history of linguistics is nay impossible. Luckily, I bumped into somebody I had vaguely known in Oxford (Robert Dingwall) and who was now a sociology professor in Nottingham putting together a research group. This became the Institute for Science and Society where we studied the social, legal, cultural, linguistic and ethical dimensions of all areas of bioscience and biotechnology.

That’s how I ended up becoming interested in public understanding of science and science communication. And from 2012 onwards my passion became writing blog posts about science and culture for the ‘Making Science Public’ blog, for which I am now writing this post….

From science communication to symbolist poets

My focus within the research group became the study of metaphors as cultural, social, political framing devices and how they are used in the media, in policy documents and wider society. Together with many colleagues from Nottingham and elsewhere I looked at the metaphorical framing of cloning, stem cells, GM, infectious disease (foot and mouth disease, SARS, bird flu, HIV/AIDS, Covid, Mpox etc.), genomics, synthetic biology, epigenetics, gene drive and bionanotech.

The early 2000s were heady days for nanotech and its popularisation through images of nanobots that were supposed to travel through our bodies to cure and heal. So, in 2005 I published an article on nanobots in their cultural contexts, from Jules Verne’s 1871 fictional submarine the Nautilus to the Proteus in the 1966 film Fantastic Voyage that swam through our blood stream. I also quoted a line from Rimbaud’s 1873 poem “Impossible”: “Ah! Science never goes fast enough for us!”

This could still be the motto for much of the science we see today, from genomics to artificial intelligence and the combination between the two. I am glad the invisible thread that I only now discovered led me to where I am now and all the fun I can still have with science, symbols and metaphors.

Footnote

*One rather sad note: Roy Harris later published a book on Saussure and Wittgenstein as sole author, a book on which we had initially worked together…..

Leave a comment