A couple of weeks ago, I told my former colleague Sujatha Raman that I was collecting metaphors for AI, such as AI slop for example. She asked: “Have you heard about AI veganism?” I said no, I hadn’t, whereupon she sent me an article from The Guardian and that set me off down a rabbit hole.

As I said in my post about AI slop, there are a lot of lexical combinations, so-called lexical compounds, appearing around ‘AI’. Think about AI literacy, AI native, AI detector, AI tutors, AI assistant, AI apocalypse, AI sceptic and thousands of others – and to this list one can add now ‘AI vegan’ and ‘AI veganism’. But what does this lexical compound and metaphor mean, what issues around AI does it highlight and hide?

Two metaphors, two discourses

When I started to think about this, I thought back to a project about lexical compounds used in climate change discourses. We called them ‘carbon compounds‘, as they clustered around the word ‘carbon’ – carbon market, carbon offset, carbon cowboy and, of course, the most central of them all, carbon footprint. We wrote an article about one of these carbon compounds that was, like carbon footprint, intended to get individuals to reduce their carbon (fossil fuel) consumption. That compound was ‘low carbon diet’. Like ‘AI veganism’ it was a food or dietary metaphor.

We, that is, Nelya Koteyko, Vyvyan Evans and I, analysed its pros and cons in a 2011 article. We argued that on the one hand this metaphor brought something complex and global down to ‘human scale’. It connected dietary choices (such as reducing meat, eating seasonal food, reducing waste) directly to the broader, often overwhelming, goal of reducing greenhouse gases, thus providing a space for individual or community action. On the other hand, this diet metaphor shifted the focus away from systemic, industrial, and government-led changes to individual consumer choices and household energy management.

Now we live in different times. Climate change is still a complex global issue, made even more complex by the advent of generative AI and the building of energy and water hungry infrastructures. The question is what does ‘AI veganism’ mean in this context? Is this the new ‘low carbon diet’ of the AI era? So far nobody has made the link between the two metaphors. In this post I’ll first chart the emergence of the AI veganism metaphor and its discussion in the media, before exploring how it reproduces the same tensions we identified in low carbon diet discourses – empowering individual choice while potentially obscuring systemic problems.

Origins and meanings

The idea of an AI vegan is someone who abstains from using AI, the same way a vegan is someone who abstains from eating products derived from animals. This should not be confused with AI generated vegan recipes or embracing AI to enhance veganism.

In the past few years, various terms have been used to describe the attitudes of people who avoid using AI: ‘AI reluctance’, ‘AI hesitancy’ (echoing the phrase ‘vaccine hesitancy’) or ‘AI abstinence’ (similar to abstaining from alcohol or sex). The people themselves can be called ‘AI sceptics’ or more pejoratively ‘AI luddites’ or ‘AI phobics’.

The phrase ‘AI veganism’ was first prominently used by David Joyner, an online education expert, in an article for The Conversation published on 29 July 2025 entitled “‘AI veganism’: Some people’s issues with AI parallel vegans’ concerns about diet”.

He made the point that just as vegans have ethical, environmental and personal wellbeing concerns about what food they consume, so AI vegans might have concerns about AI consumption spanning ethical (exploitation and consent), environmental (resource consumption) and well-being concerns (especially regarding critical thinking and mental health). They might therefore choose to avoid AI tools like generative chatbots or image creators, to use them only sparingly and selectively, or to boycott their use altogether.

Although Joyner brought the term to public attention, he notes in a LinkedIn post that it has an earlier history, referring to “a HackerNews thread from 2022 that threw out the term”, which went unnoticed. The term seems to have been in the air in June/July 2025 though: “Three days after I pitched that idea, Joe McKay posted a video about going AI vegan as a company, with a couple fascinating follow-ups. There was also a Medium article about the idea published on July 7.”

That Medium article, entitled “AI Veganism: A New Ethic for the Algorithmic Age”, argues that ‘green AI’ might be a better option than ‘no AI’. This might include ‘offsetting’ AI usage, which reminds me of the carbon compound ‘carbon offsetting’ – a practice that ran into ethical problems, encapsulated by the phrase ‘carbon indulgence’, the controversial practice of purchasing carbon offsets to compensate for high-emission activities.

Now there is a whole Wikipedia article about this phenomenon, newspapers have picked it up, and it is discussed on social media, including Bluesky. I can’t survey it all, but in what follows, I’ll look briefly at how different media outlets frame the phenomenon, then examine how people discuss and critique it on social media.

AI veganism in the traditional media

Media coverage reveals how contested this metaphor is. Different outlets mobilise ‘AI veganism’ to advance different agendas, from dismissive mockery to genuine exploration of ethical tech consumption, sometimes both in one.

The Guardian article that started me on my journey into the rabbit hole is entitled “Meet the AI vegans” and its author Arwa Mahdawi, asks: “Will AI veganism catch on?” The answer is quite snarky, playing on stereotypes of vegans: “Who knows. But, just like regular veganism, I’m sure its practitioners will tell you about it.” Ed Winters, a vegan educatior, criticised this tone, pointing out that “people are already looking for any reason to dislike veganism and the word ‘vegan’, so applying it to situations which are going to elicit eye rolls is just offering more of an excuse to associate the word ‘vegan’ with something negative.”

However, Mahdawi also makes a more substantive point: “while it may be unrealistic to expect the masses to go digitally vegan, it’s not a bad idea for us all to be more cognisant of how much AI we consume and its impact on the planet. Perhaps any request to AI apps should be met with a digital calorie count first?” This suggestion – that we should see the environmental cost of each query – directly parallels the low carbon diet movement’s emphasis on making carbon footprints visible and actionable.

Euronews takes a more sympathetic approach, interviewing actual AI vegans who express deep concern about AI ethics and the possible decline in critical thinking. One of them warns that “having people be dumb while the chatbots tell them how right and brilliant they are? That’s worrying.”

In a New Scientist article “Escaping the Anslopocene” (title of the print version), Rowan Hooper takes a playful sci-fi approach and imagines the invention of DumbGlasses – the opposite of smart glasses – which let you see unaugmented reality and detect AI slop. “Some wearers celebrated their status with T-shirts and badges bearing slogans such as ‘AI Vegan’, ‘Real or Nothing’ and ‘Slop-Free Zone’” – linking up, yet again, the AI slop and AI vegan metaphors.

The Mirror, predictably, takes a more dismissive stance, describing ‘AI veganism’ as a “growing online movement of generative AI phobics, ‘AI vegans’, who are determined to abstain from the technology no matter the cost” – casting such people as irrational.

More pragmatically, the Indian Economic Times points out that because some AI sceptics may never adopt the technology, there are opportunities for niche markets offering products marketed as “AI free”, similar, I suppose, to meat-free or GM-free products.

AI veganism on social media

A cursory search of Bluesky (more research needed!) reveals three main themes in how people discuss AI veganism online: debates about whether the metaphor even works, questions of identity and social stigma, and extensions of the analogy to think about AI production systems.

Does the metaphor work?

Some commenters reject the metaphor entirely. One said: “Oh gosh, I see the term ‘AI veganism’ popping up in newspapers because some dude used it to describe people who do not consume AI and draws parallels with veganism. It totally fails to describe why some people do not want it. If I refuse to use pesticides, am I a ‘pesticide vegan’?”

Others see merit in the term but express despair about whether individual choices can address systemic problems – the same contradiction that plagued the low carbon diet movement: “Being anti ai is starting to feel like a vegetarian/vegan, sure im not partaking but it isnt stopping the millions of ai produced art, answers, conversations, etc.”

Identity politics and social stigma

Several commenters noted how both vegans and AI sceptics face similar social dismissal (see the original Guardian article). “Being anti AI is a lot like being vegan. You’re objectively correct but the people who don’t care are gonna complain about how annoying you are for pointing out the harms caused and issues it creates.”

Others linked resistance to both veganism and AI veganism to masculinity: “funny how the same dudes that hate veganism and vegan food and go ‘I only real meat, like a manly man’ the same type of dudes who love AI slop.” This also links resistance to AI in terms of veganism to resistance to AI slop.

One commenter highlighted how the term itself functions as rhetoric: “The Propaganda on AI stuff is wild, literally saw the term ‘AI Vegans’ to describe people who don’t want to use AI. Regardless of your stance on Veganism, this is clearly worded to evoke disgust to the general populace.” The metaphor works both to create identity categories and communities of practice, and to reinforce ingroup-outgroup polarisation.

The vegan framing also appears in how users interact with each other. One commenter recounted being “accused of ‘serving meat to a vegan’” when submitting Claude-generated output. Another said: “finding out AI was in a game i enjoyed feels like when people ‘prank’ vegetarians by sneaking bacon grease into their food or whatever.”

Industry and production

Some commenters extended the metaphor to think about AI production systems, drawing parallels with factory farming: “If we view generative AI as the meat industry in this analogy I’d compare shit like arc raiders or e33 as the equivalent of ‘organic/free range’ farms in that there’s some argument for ethics and quality but it’s still contributing to the larger issues at hand, and the core problem isn’t addressed.”

This brings us to the central tension: whether changes in individual consumption of either food or AI can address the bigger structural issues around climate change, corporate power, and environmental harm.

Two metaphors, one dilemma

Both ‘AI veganism’ and ‘low carbon diet’ are part of the ethical consumption movement. They bring complex global problems down to human scale by linking them to individual choices. And crucially, they overlap in their environmental concerns: vegans worry about the carbon footprint of the meat industry, while AI vegans worry about the carbon footprint of the AI industry.

The Guardian‘s suggestion that “any request to AI apps should be met with a digital calorie count first” perfectly captures this parallel. Every AI interaction has a ‘hidden carbon story‘, much like food has a carbon footprint. Both metaphors encourage us to consider the environmental cost before consuming.

However, as all metaphors do, these too highlight and hide at the same time. They highlight individual agency and provide actionable choices. They empower people to make ethical decisions about their consumption. But they also potentially hide systemic failures and obscure questions of corporate responsibility and regulatory action.

This risks letting the real drivers off the hook. Microsoft, Google, and Meta are building massive data centres regardless of whether individuals choose to use ChatGPT. The AI industry’s energy and water consumption is driven by corporate decisions about infrastructure and scale, not by individual queries. Similarly, industrial agriculture’s environmental impact isn’t primarily driven by individual dietary choices, but by policy decisions, subsidies, and corporate practices.

The low carbon diet movement faced this exact dilemma. As our 2011 article argued, while the metaphor empowered individuals and made climate action feel achievable, it also shifted the focus away from regulation of fossil fuel industries and investment in renewable infrastructure.

AI veganism risks reproducing this pattern. Individuals choosing not to use AI tools, while ethically coherent, won’t address the fundamental questions about how AI systems are built, who controls them, what energy sources power them, and whether their development serves genuine social needs or primarily corporate profit.

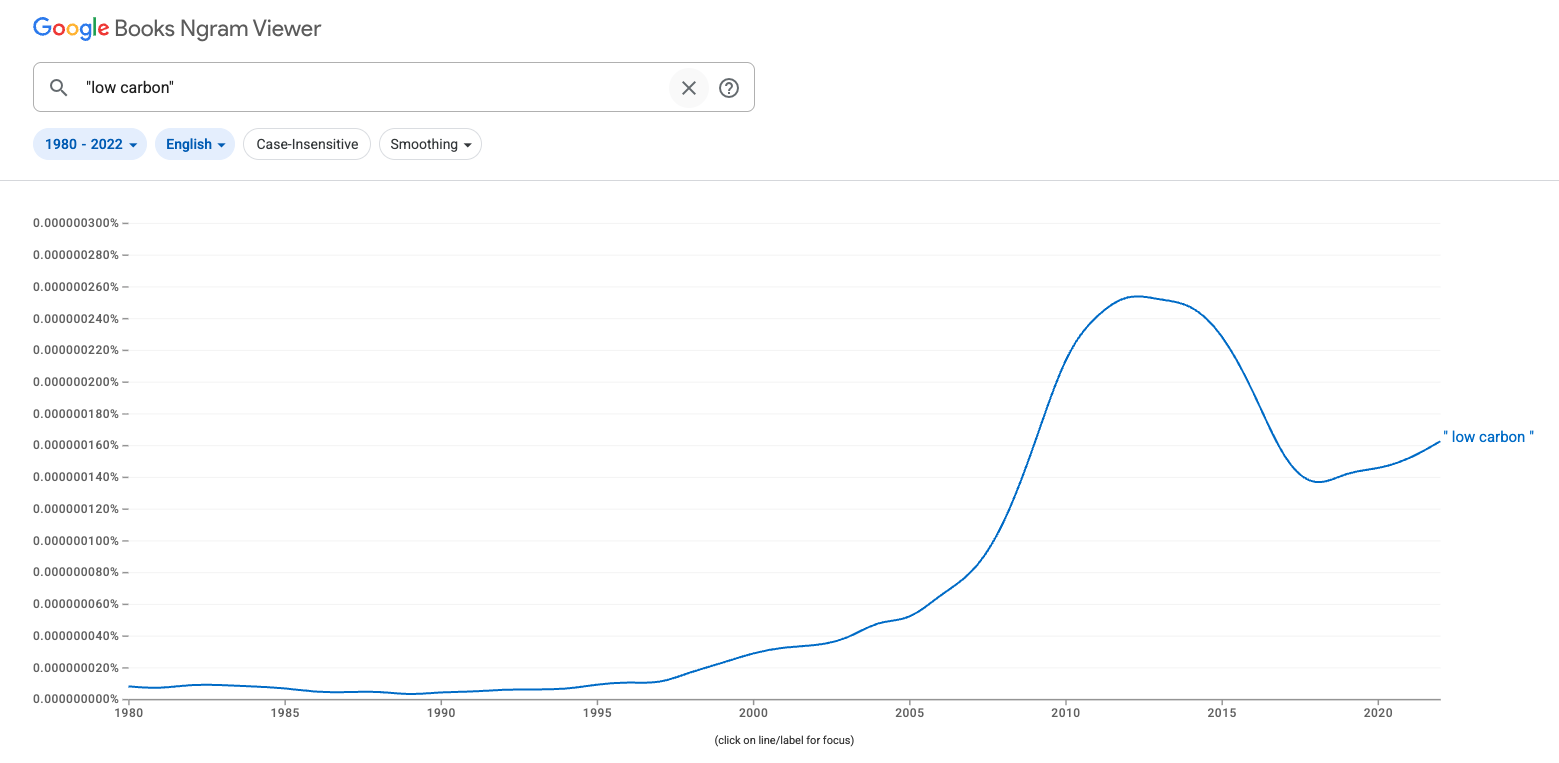

The following graph from Google Ngram Viewer shows that the ‘low carbon’ discourse peaked around 2011 – just when we wrote our article – and then declined (what did we do? ;)). There was disillusionment with the low carbon movement after that, perhaps because individual action alone proved insufficient to address climate change. There seems to be a slight revival now.

What happened to low carbon diet?

AI veganism will likely never reach such levels of uptake. Unlike the low carbon discourse, which was promoted by institutions and policymakers for a time, AI veganism appears to be a grassroots phenomenon, which may limit its reach. Whether it faces a similar trajectory – initial enthusiasm followed by disillusionment – remains to be seen.

What both metaphors reveal is how we try to make sense of overwhelming technological and environmental challenges by connecting them to the most intimate and immediate choices we make: what we eat, what tools we use, how we live our daily lives. These metaphors matter because they shape how we understand our agency and responsibility. But they also matter because of what they leave unsaid – the harder questions about identity, stigma, power, politics, and structural change that individual consumption choices, however ethical, cannot answer alone.

Image: Cucumber plants in hydroponic greenhouse

Leave a comment