The other day I was talking with a friend and moaning about writer’s block. My friend said: “You are into words and metaphors and stuff. What’s one small language puzzle that’s been nagging at you lately?” I blurted out: ‘vibes’. My friend replied: “Write about that then”.

Lots of people have written about that word recently, especially it seems about ‘the politics of vibes’, but haven’t perhaps engaged in what one might call conceptual history. So, in this post I’ll sign-post some stages in the semantic development of that word as it has shifted from music to feelings to politics, from ‘good vibes, man’ to ‘vibes-based voting’, mirroring profound changes in culture and society.

From music to feelings

Let’s start at the beginning which means have a look at the Oxford English Dictionary. It seems that in the 1940s two words began to ‘vibe’ together, namely the word ‘vibraphone’, a new sort of musical instrument shortened to ‘vibes’, and the word ‘vibration’ (of sound). So, we hear about “some too-formal ensemble riffing with vibes” in 1940 and ten years later about a bass saxophonist who had been “concentrating on vibes since the early 1930s”. The word was embedded in the jazz and music culture of that time.

In the 1960s, young people began to talk about good and bad vibes or vibrations in the sense of sensing, quite instinctively, the positive or negative atmosphere or ‘energy’ surrounding people or objects. The 1967 song “Good Vibrations” by the Beach Boys encapsulated that meaning and by “1970, John Lennon was saying it (“You give off bad vibes”), then Bruce Springsteen (“Hey vibes man!”), and, by 1983, Kate Bush (“Vibes in the sky invite you to dine”, in Blow Away)” (see nice overview article in The Guardian).

In 1968 the Los Angeles Times first used the word vibe as a verb “It’s Saturday 10:30 showtime and the Troubadour is vibing with that excited crowdedness so dear to the hearts of nightclub owners” (OED).

In the early 2000s ‘vibing’ (or ‘vibin’) began to be used more frequently by another generation of young people (Gen Z) in the sense of “relaxing, tapping into good feelings, and just generally enjoying the atmosphere” or a relationship. Similar to the 1960s, it was all about “authenticity and emotional resonance”.

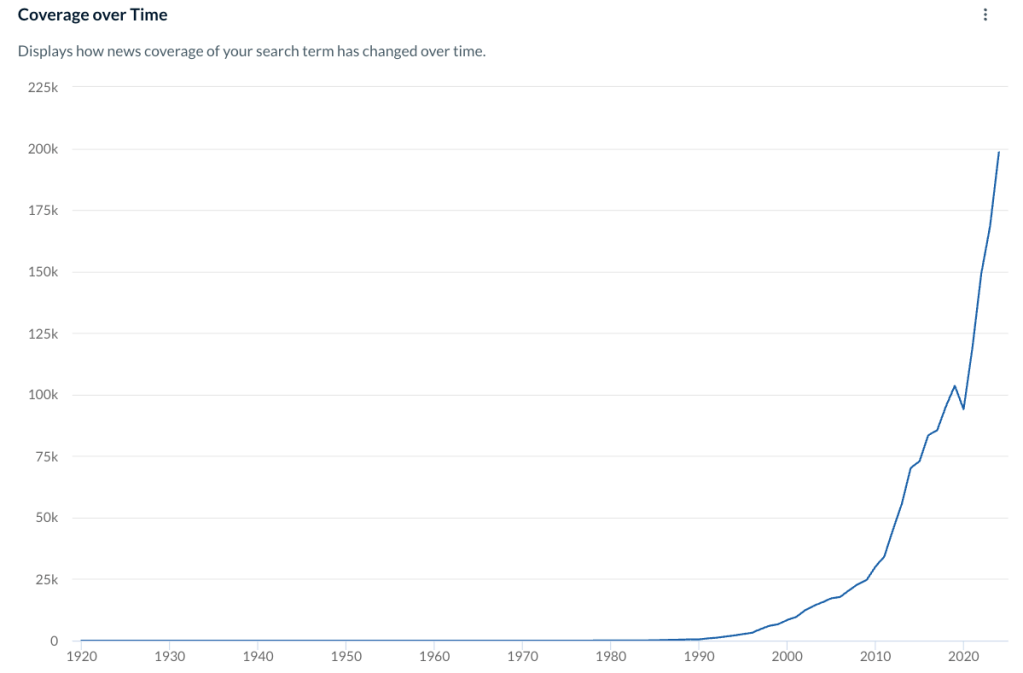

What happened next? Let’s have a quick look at some stats. On Google Ngram Viewer we can see that the word ‘vibe’ took off in the year 2000 and there was also a sudden explosion of phrases around vibe, such as vibe with, off, of, in, to and so on. Google Trends shows that the word ‘vibes’ began to trend upwards in 2016. A look at the newspaper database Nexis shows an increase in the use of ‘vibe’ from around 1990 onwards with a steep uptick around 2021.

2016 was the time of Brexit and the first incarnation of Trump, but also the time of ‘post-truth’ (the OED’s word of the year in 2016), when feelings began to be more important than facts. Then came the pandemic, and in 2021, when we finally had a vaccine and people could leave their houses, Sean Monahan coined the word ‘vibe shift’. This phrase went viral and became somewhat synonymous with a shift in trends. The word ‘vibe’ became a trend-setter itself.

But, of course, a successful word doesn’t only take off and spin off phrases and meanings, a sticky word can also spread to other languages and be taken up as a loan word. In German, for example, we have ‘vibe’ and ‘vibes’ and can say ‘ich vibe’. I found this great sentence on Bluesky which absolutely captures the stereotypical vibe of the German language together with its tendency to borrow words from English: ”schienenersatzverkehr ist einfach das perfekte wort um schienenersatzverkehr zu beschreiben es trifft den vibe von schienenersatzverkehr zu 100%” (rail replacement service is simply the perfect word to describe rail replacement service it captures the vibe of rail replacement service 100%).

We can now talk about the ‘vibe’ of a political campaign, the ‘vibe’ of economic data, the ‘vibe’ of scientific findings, and of course of rail replacement services. The word now covers everything from literal sound waves to a general sense-making tool. When people say, “these climate data have a really ominous vibe”, they are not being scientifically rigorous, but they are capturing something that raw statistics might miss – the gestalt, the emotional undertone, the intuitive reading of complex information.

From feelings to algorithms

That’s all very nice and positive, but unfortunately, the word vibe has been captured in the maelstrom of the social media and algorithmic marketing and manipulation revolution. We all know how we are algorithmically manipulated on YouTube and TikTok and so on. Marketeers basically ‘tune the vibe’ on digital platforms.

According to a recent article, “digital platforms’ targeted advertising is more productively understood as tuned advertising, where algorithmic models optimize the resonance between ads and consumers in a continuous rhythmic flow of images, videos, and text”. Here the ‘Iines between content and advertisements’ are blurred to create an ‘uninterrupted mediated feeling’” – vibes all the way down. This has repercussions for politics, as many ads feed political values and biases, from diversity in the past to patriotism now.

With the advent of AI in around 2022, vibes and vibing have become even more serious business and, like AI, all-pervasive. You can now aspire to become be a ‘vibe manager’ or a ‘head of vibe’ in some tech firms. As Jess Cartner-Morley wrote in a fascinating article on vibes for The Guardian: “Facts are dead, and the vibe is king.”

We now also have ‘vibe coding’.* As one blogger explains: “After a post by Andrej Karpathy went viral, ‘vibe coding’ became the buzzword of the year [2025] —or at least the first quarter. It means programming exclusively with AI, without looking at or touching the code. If it doesn’t work, you have the AI try again, perhaps with a modified prompt that explains what went wrong.” Google may now adopt vibe coding for search algorithms….

Over time, vibe has been turned into a marketing tool, even a product, and a tool for manipulation. A word that was once synonymous with ‘peace and love’ has somehow become economically and politically weaponised.

This is particular worrying with regard to the word ‘vibe check’ which was once used to mean that one makes an assessment of the ‘vibe’ (feeling) of a place or a person (Google Maps can get you a vibe check before you visit a place), but can now refer to a rather brutal sort of policing, as ‘vibe check’ has become a metaphor for TSA (US Transport Security Association) screening and profiling.

From algorithms to politics

This has, of course repercussions for society and politics. In a society where life, the universe and everything is based on vibes rather than reality, substantive political issues and values no longer matter. As a blogger said as early as 2022: “On both sides of the Atlantic, there’s a debate going on between [those] invested in theories of the tangible – policy or issues – and those who increasingly believe it’s the intangible. The ‘atmospherics’ of cultural and tribal markers; personality. That is, vibes.”

He talks of a vibes-based theory of politics, indeed ‘vibology’. Such vibes-based politics has become increasingly influential at a time when vibes-based AI and social media algorithms can lead to what some call ‘algorithmic radicalisation’. It’s all about ‘vibes and tribes’.

A blog entitled “Trapped in the Algorithm: Gen Z’s Journey into Conservative Content”, starts with a quick summary of the article’s main arguments. In scientific journal articles this would be called ‘highlights’. Here it’s called ‘Quick Vibes’, in the sense of getting a feel for the article. And of course, the article starts with a scenario that goes like this: “Picture this: you’re mindlessly scrolling through TikTok, laughing at relatable skits, vibing to sped-up songs, and maybe hitting like on a ‘hot takes’ video about school or gas prices. Then, gradually, without even noticing, your ‘For You Page’ starts shifting.” Here we are back to ‘vibing to’ as meaning experiencing a positive and relaxed feeling while listening to or watching something.

Conclusion

What have we found out about vibes on this conceptual journey? We have seen a shift in meaning (a vibe shift!) from vibes referring to musical instruments and physical and measurable sounds to real but subjective and intuitive gut feelings. More recently, one can observe a shift from vibes as real and subjective feelings to vibes as manufactured feelings, that is, artificial vibrations designed to feel real. The meaning of vibes has spread across the domains of music and moods, to moods being captured by algorithms to algorithms manipulating moods and politics.

In terms of semantic change, we can see a general trend in ‘generalisation’, that is, a gradual and recently more rapid broadening of meaning, but also some ‘pejoration’, when, for example ‘vibe check’ is metaphorically used in a rather negative way. These semantic changes reflect, indeed resonate with, profound cultural, political and technological changes. But all the meanings are still there, even the ones relating to feeling the good vibrations of peace and love and harmony. We should not forget that.

I hope I have captured some of the vibrations of the word ‘vibe’ and that we can still create good vibes together.

PS. Since I wrote this last summer the vibes have exploded, especially with the advent of coding agents, so much so that Stephen McGann can now say (29 January, 2026) “A sure sign of my age is that I don’t employ the word ‘vibe’ as a linguistic swiss army knife.” NICE metaphor!

Footnote

* Really good info on ‘vibe’ coding can be found on the Oscillator Blog!

NOTE

When I started on this conceptual journey I didn’t know what I was letting myself in for. There is so much out there! One could write a book about it. And, haha, somebody has! Robin James: Good Vibes Only, which will be coming out soon.

There are also two long Guardian articles that are worth a read and which inspired some of my thinking, one by Jess Cartner-Morley and the other by Naaman Zhoo.

Image: Needpix.com

Leave a reply to Making Science Public 2025: End-of-year round-up of blog posts – Making Science Public Cancel reply