I have followed the emergence of recent developments in AI from the end of 2022 onwards, marked by the launch of OpenAI‘s AI chatbot ChatGPT. It’s now the middle of 2025 and a LOT has happened in this space. From being a niche and nerdy topic, AI has become a topic discussed across society.

Recently, I have observed people musing, applauding, warning about an ‘AI bubble’ on Bluesky, especially after Sam Altman, CEO of Open AI, talked about it and compared it to the dot-com bubble of the 1990s. Shrewd observers then asked whether we were talking about a bubble in AI technology or in AI markets and whether it’s more comparable to the tulip bulb mania of the 1630s or the railway mania of the 1840s. Others pointed out that the dot-com bubble didn’t make the internet obsolete…..

In this post I will not contribute to these clever discussions but just do what I sometimes do, that is, engage in some conceptual archaeology, focusing on the two metaphorical phrases ‘AI winter’ and ‘AI bubble’, which themselves are surrounded by a penumbra of metaphors such as bursting, crashing, stalling, popping, puncturing, wobbling, deflating, freezing and so on and also by related phrases like AI hype, AI boom and even AI con.

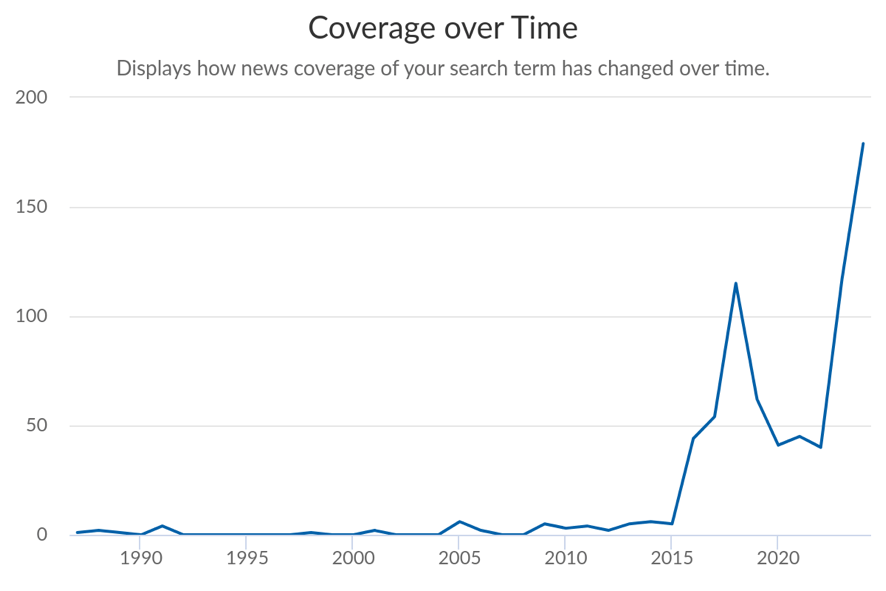

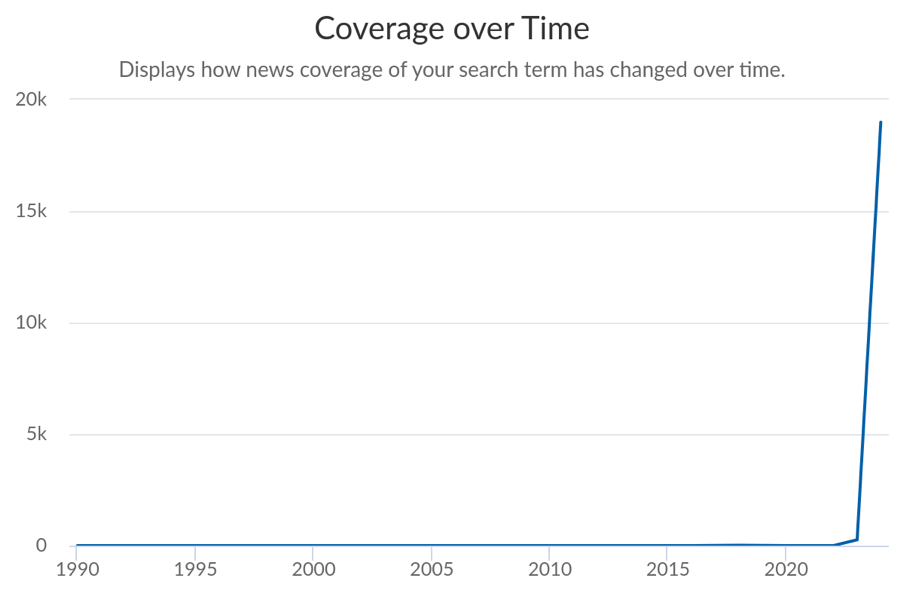

Almost all the phrases I mentioned (AI hype, boom, bubble, winter) are older than you might think, with AI winter being the oldest, as there was already talk of such a winter in the 1970s, and the others making their way into our language during the 1980s. They all have risen in prominence after the 2022 AI explosion, as this Google Trends graph shows.

In the following I explore the meaning and history of the two metaphors ‘AI winter’ and ‘AI bubble’, which are of course both linked to AI hype, as hype leads to winter and to bubble bursting – the typical hype disillusionment cycle (you can learn more about hype here and about the long history of AI hype here).

AI winter

The phrase AI winter is not yet recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary, but it has an entry in Wikipedia. It has an interesting history.

As people know, the term AI was coined in 1956, when I was born, during an era of intense AI optimism. In 1974, when I went to university, a first slow-down in AI excitement began and lasted until 1980. In 1984, when I first encountered ‘computers’, Marvin Minsky and Roger Schank warned of a looming ‘AI winter’ (actually a second winter), drawing an analogy with the concept of a nuclear winter. Another AI winter lasted from 1987 to 2000, and there were a few other frosty periods after that. Now there is talk of another winter.

What is an AI winter – what does the metaphor mean? It refers to a period of relative quiet, of inactivity and pessimism around AI research and development, a period when it’s also said to be ‘dormant’. The winter framing can come to the fore in headlines like this from 24 August 2025: “The chill before the storm: Why AI’s hype could freeze over” (The Tribune).

When we look at the uptake of the phrase ‘AI winter’ in English News discourse overall (using the Nexis database), we can see that the phrase only really began to gain traction around 2015, with a peak in 2016 followed by another bigger peak from 2022 onwards.

2016 was an important year in AI development, especially machine learning. A Guardian headline declared: “2016: the year AI came of age”. Others proclaimed the latest AI winter to be over. English news went a bit quiet after that but as soon as ChatGPT was released there was talk again about an AI winter alongside, ironically, talk of an AI boom. Now there is talk of doom and bubbles bursting. Let’s have a look at the interesting phrase ‘AI bubble’.

AI bubble

The term ‘AI bubble’ seems to be quite young – I can’t find any indications about when it was first used and by whom. It “refers to the idea that the current enthusiasm, investment, and valuation surrounding artificial intelligence (AI) technologies might be inflated beyond their actual value or sustainable growth potential”. But why ‘bubble’? Now that word has some history and it’s more interesting than I thought.

The Oxford English Dictionary records a figurative meaning of bubble, as “An insubstantial, delusive, or fraudulent project or enterprise, esp. of a commercial or financial nature” and gives as one example the South Sea Bubble. There were other bubbles too, such as the the Dot-com bubble, the Cryptocurrency Bubble and many more. The image conjures up a soap bubble that inflates and then bursts.

Apparently, the figurative meaning of bubble was first used by the satirist Edward Ward (commonly known as Ned Ward) who wrote in 1700: “I’m like to make a very hopeful Bargain this Morning; and grow Rich like a Jacobite, that would part with his Property, for a Speculative Bubble”. He later wrote a satirical poem entitled “A South-Sea Ballad, Or, Merry Remarks Upon Exchange-Alley Bubbles.”

After that it gets even more interesting. In 1721 Jonathan Swift wrote in his satirical poem “The Bubble“: “The Nation..will find..South-Sea at best a mighty Bubble.” And in 1727 Daniel Defoe wrote: “In the good old days of Trade..there were no Bubbles, no Stock-jobbing.” This was written in the context of the South Sea Bubble, one of the most famous and infamous financial crashes that happened in 1720 (it’s worth reading this Wikipedia article!) The financial bubble metaphor spread widely, a history charted here by Ben Zimmer.

What about present times? In 1950 English news (in the Nexis database) first used the word ‘bubble’ with relation to markets, talking about the “bubble and boom” of the great depression. The use of ‘bubble’ increases after 2000. ‘AI bubble’ is first used in its current sense around 2015 and 2016, when, as we saw, AI went mainstream.

Do you remember Roger Schank, who with Minsky, coined the term ‘AI winter’ in 1984? He pops up again in 2016 in an article in New Scientist (16 July) about the misuse of the phrase ‘artificial intelligence’: “It’s not just semantics. Tell people a machine is thinking, and they will assume it is thinking the way they do – and can distinguish, for example, a white van from a bright sky, as a self-driving car failed to do in May. This mismatch can have serious – or in the case of the car, fatal – results. If it happens enough, it could pop the AI bubble (see main article). ‘The beginning and the end of the problem is the term AI,’ says Schank. ‘Can we just call it ‘cool things we do with computers?’” I really wish we had heeded Schank’s advice!

The main article referenced here is also from 2016 and entitled “Will AI’s bubble pop? Deep learning’s hype machine in overdrive”. We are still having these discussions today, with the ‘AI bubble’ really bursting onto the English news scene in 2023.

I’ll only quote from one recent article (there are thousands!) which displays a wonderful mix of metaphors: “For the past few years, the artificial intelligence juggernaut has been charging through the global economy, seemingly unstoppable. […] Yet, as with every bubble, the brakes are now beginning to screech. The once-rapid leaps in model complexity have slowed, signalling a plateau in the technology’s development. The question looming over investors and technologists alike is whether the AI boom will end in a burst.” (The Nation, 22 August 2025)

Where will the discussion about AI winters and bubbles go? I wonder whether anybody will write satirical poems about them, like Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope did at the beginning of the 18th century, when ‘bubbles’, ‘anti-bubbles’, ‘hubble bubble’ and much more were all the rage.

A writer calling himself Anti-bubble, who is most likely Defoe, wrote in 1719: “Now, good Mr. Journalist, tell us, since Bubbles are so much in Fashion, what Bubble will come upon the Stage next? and how must an honest Man do among them all, that he may not be bubbled out of his Money?” That is a good question!

AI winter and AI bubble – some open questions

Both the AI winter and Ai bubble metaphors have had interesting ‘lives’ and there is so much more one could explore. I’ll just highlight a few things that are intriguing or puzzling.

Although coming after the first period of AI hibernation and being coined in 1984, the phrase ‘AI winter’ didn’t really gain wider currency during subsequent winters. It seems to have hibernated until AI really started to heat up recently. Can it be that the phrase only became useful for journalists and commentators once there was enough general awareness of AI to make the metaphor meaningful and useful to readers?

The dual peaks of ‘AI bubble’ discourse in 2015/16 and after 2022/23 are interesting. The 2015/2016 discussions coincide with AlphaGo and deep learning breakthroughs and prompted headlines of AI coming of age. That was when the tech world started getting genuinely excited (and nervous) about AI capabilities. But then the 2023 explosion after ChatGPT represents something different, namely mass public engagement and anxiety.

The 2016 ‘AI bubble’ talk might have been more about venture capital and tech industry hype, while 2023 and current version are more about public excitement and public worries. Might it be that the bubble metaphor functions differently in different contexts and for different audiences? That deserves more exploration.

And then there is AGI – AGI winters and bubbles deserve a separate treatment….

Epilogue

I can’t resist closing with another quote from Swift’s “Bubble” poem – echoing Shakespeare’s song of the witches and using the word ‘computing’. I’ll replace Swift’s phrase ‘South Sea’ with ‘AI’:

“The nation then too late will find,

Computing all their cost and trouble,

Directors’ promises but wind,

AI at best a mighty bubble.”

Image: PickPik

Leave a reply to Making the case for an AI metaphor observatory – Making Science Public Cancel reply